Oral Traditions in Greater Mexico

Marcia Farr

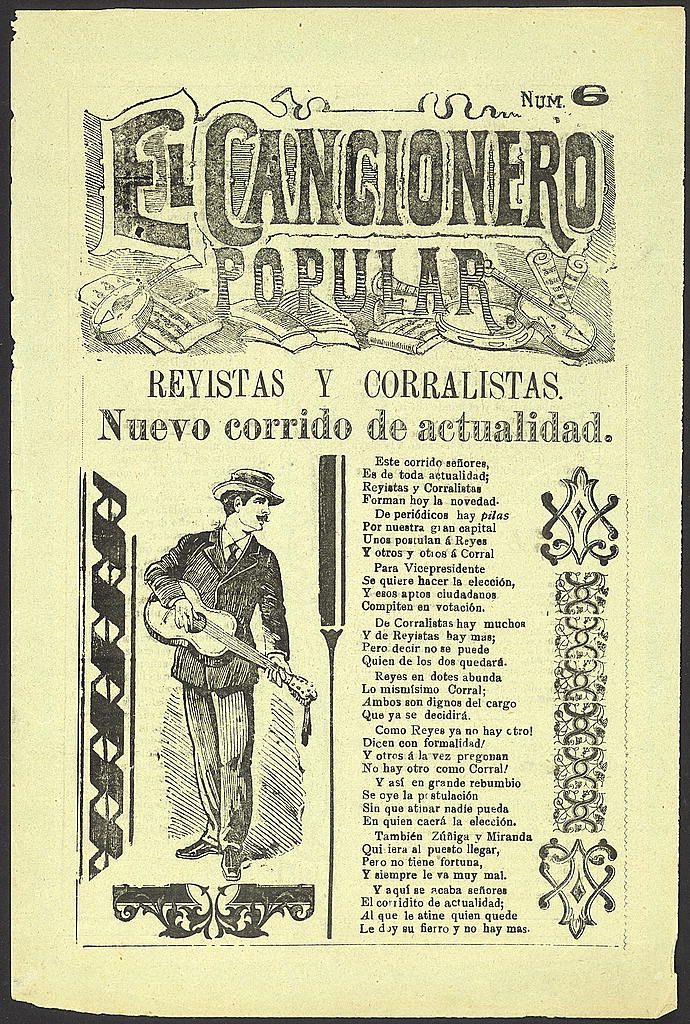

What Américo Paredes (1993) once called Greater Mexico now exists all over the United States. That is, the Mexican diaspora (perhaps Cuauhtémoc’s true revenge) is evident from Alaska to Georgia, and everywhere in between. This presence of Mexicans is particularly notable in Chicago, the global Midwestern city, which now counts a million persons of Mexican descent in its metropolitan area (U.S. Census 2000). Mexicans, like all peoples, bring their oral traditions with them in such transnational migrations. Mexican oral traditions rely on a wide range of genres, from the more canonical corridos (narrative folk songs with poetic structuring; see HerreraSobek 1990, Limón 1992), proverbs (Dominguez Barajas 2002), riddles, and jokes to varying types of informal narratives. The richness of these oral traditions illustrates the creativity and high value placed on rhetorical competence (Briggs 1988) within Mexican cultures and the importance of the poetic in Mexican verbal art and life. Although demographers, sociologists, and anthropologists have studied transnational Mexican communities, little work has focused on oral traditions within these populations (Farr 1994, 1998, 2000, in press; Guerra 1998). Oral traditions, of course, can be performed in public, more formal settings, or in private, more intimate ones. The commercialization of corridos on CDs enables their almost constant public performance on Spanish language radio stations. At the other extreme are the intimate contexts of family and home, in which oral traditions live on the tongues of and in the space between persons, contexts that are often out of the range of interested researchers. My deep involvement with a social network of Mexican families, both in Chicago and in their rancho (rural hamlet) in northwest Michoacán, over the last decade and a half has given me access to such intimate contexts, and especially to all-female conversations within them. The developing awareness over recent decades of the reflexivity of ethnography allows us to recognize the effect of gender and other identities on the research process. In this respect, my gender has been significant in opening access to the rich 160 MARCIA FARR world of female talk in these families, transcending other aspects of identity in importance. I have thus been able to describe three culturally embedded ways of speaking within this group:1 franqueza (frank, candid talk), respeto (respectful talk that inscribes traditional age and gender hierarchies), and relajo (joking talk that, like fiesta or carnival, turns the social order “upside down” and thus provides a space for social critique). Particularly during the verbal frame of echando relajo (joking around), women (and men) address the inevitable tensions of the existing social order, frequently treating gender with a humorous critique. In the storytelling that abounds during relajo, people construct their politics with poetry, utilizing parallelism, repetition, quoted dialogue, and other oral poetic devices that persuade through aesthetic pleasure. Given the large and growing number of Mexicans in the U.S., and especially of Mexican children in schools, such portraits of verbal art can persuade teachers and others of the creativity and verbal dexterity in Mexican oral traditions, aspects of communicative competence that can be constructively built on to develop verbal skills in the academic register.

Ohio State University

References:

Briggs 1988 Charles Briggs. Competence in Performance: The Creativity of Tradition in Mexicano Verbal Art. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. Domínguez Barajas 2002 E. Domínguez Barajas. “Reconciling Cognitive Universals and Cultural Particulars: A Mexican Social Network’s Use of Proverbs.” Unpub. diss., University of Illinois at Chicago. Farr 1994 Marcia Farr. “Echando relajo: Verbal Art and Gender among Mexicanas in Chicago.” In Cultural Performances: Proceedings of the Third Women and Language Conference, April 8-10, 1994. Ed. by Mary Bucholtz et al. Berkeley, CA: University of California. pp. 168-86. 1 A book is in progress: Rancheros in Chicagoacáu: Ways of Speaking and Identity in Mexican Transnational Community. ORAL TRADITIONS IN GREATER MEXICO 161 Farr 1998 . “El relajo como microfiesta.” In Mexico en fiesta. Ed. by Herón Pérez Martínez. Zamora, Michoacán, Mexico: El Colegio de Michoacán. pp. 457-70. Farr 2000 . “¡A mí no me manda nadie! Individualism and identity in Mexican ranchero speech.” Pragmatics (special issue ed. by V. Pagliai and Marcia Farr), 10:61-85. Farr in press , ed. Latino Language and Literacy in Ethnolinguistic Chicago. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Guerra 1998 Juan Guerra. Close to Home: Oral and Literate Practices in a Transnational Mexicano Community. New York: Teachers College Press. Herrera-Sobek 1990 María Herrera-Sobek. The Mexican Corrido: A Feminist Analysis. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Limón 1992 José Eduardo Limón. Mexican Ballads, Chicano Poems: History and Influence in Mexican-American Social Poetry. Berkeley: University of California Press. Paredes and Bauman 1993 Américo Paredes and Richard Bauman. Folklore and Culture on the Texas-Mexican Border. Austin: University of Texas Press. U.S. Census 2000 http://www.nipc.cog.il.us/GDP4-counties/gdp4 _171600pmsa.pdf.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario